When I was a kid, I was fascinated with people who just picked up everything and moved to a new town or out of state. I was in awe of anyone who went abroad … like the missionaries who came to speak at our church. Having lived in a total of three places my entire life, all within about 6-7 miles apart, I’m still intrigued by others’ ability to just pick up and go.

In farming parts of the country in the 19th and 20th centuries, it wasn’t unusual for families to move at the drop of a hat. I remember Mama telling me about one of her uncles who had a whole passel of kids. They’d just up and move in the middle of the night. One day they’d be there, and the next, they’d be gone. A few months later, they might show up on some other farm a few miles away.

This would have been in the late 1950’s, 1960’s, long before I was born. (Okay, not THAT long before… ahem!) The old tarpaper shacks they lived in wasn’t much, and they wouldn’t have had much to move, but still, I can’t imagine just piling everything in a wagon (or an old beat-up jalopy of the day) and lightin’ a shuck, at least not without a good bit of thought beforehand.

They were sharecroppers. They didn’t own any land of their own, but would agree to work for a landowner in exchange for a place to live and a share of the crops grown or some other form of payment. Cash was hard to come by, so in some cases, payment might mean a cow, horse, wagon, or simply the profit from their share of crops. It wasn’t unusual for sharecroppers and tenants to work all year just to feed their family. And even that was in scarce supply some years.

Tenants and sharecroppers were similar, but also different. Tenants usually paid the landowner rent money, had their own tools, plows, and horses/mules. Obviously, the landowner and the tenant farmer could come to any agreement they chose, but the most common was that the tenant farmer would reap all the profit from the land he farmed, but he was also taking on all the risk, usually buying seed, feed, fertilizer, etc. on credit.

Sharecroppers might have nothing more than a few changes of clothes and a bit of furniture. They depended on the landowner to supply everything needed to farm, and they received a percentage of the profit from the crops only after the crops were sold. If the crops failed, everybody lost… and it was going to be a hard winter.

There were good, honest, and fair landowners, and there were those who preyed on the poor. There were good, honest, hardworking tenants and sharecroppers and there were those who took advantage of their employer (the landowner). It was a beautiful thing when honest men and women on both sides paired up and became successful together.

Besides my husband, my father was one of the most hardworking men I ever knew. He pulled himself up by his bootstraps. He started out with nothing in the fifties. Married to my mother at 18, they were young (so young!), poor, and hungry, but they were hard workers. They had a couple of good experiences and a few not so good ones as sharecroppers.

My parents came in on the end of the tenant/sharecropper period in Mississippi. In the mid-20th century, landowners took advantage of new technology and began replacing tenant farmers and sharecroppers with tractors, cultivators, disks, cotton pickers, harvesters, and pesticides.

Yes, it was a hard life, but life was hard on most everybody back then, and they didn’t really know any different. But even as hard as it was, my parents used their skills, determination and desire to make something of themselves. By the time I was born, they’d managed to purchase 60 acres of land, were in the process of clearing it and had started a Grade “C” dairy farm with a handful of Jersey cows. A few years later, they switched to Grade “A” milk. When Daddy passed away suddenly at the young age of 54, they had a thriving dairy farm and a herd of beef cattle.

Daddy and Mama were truly part of the American Dream, made possible by sharecropping.

So, did you move around a lot as a kid? As an adult? Any sharecroppers in your family? Tenant farmers?

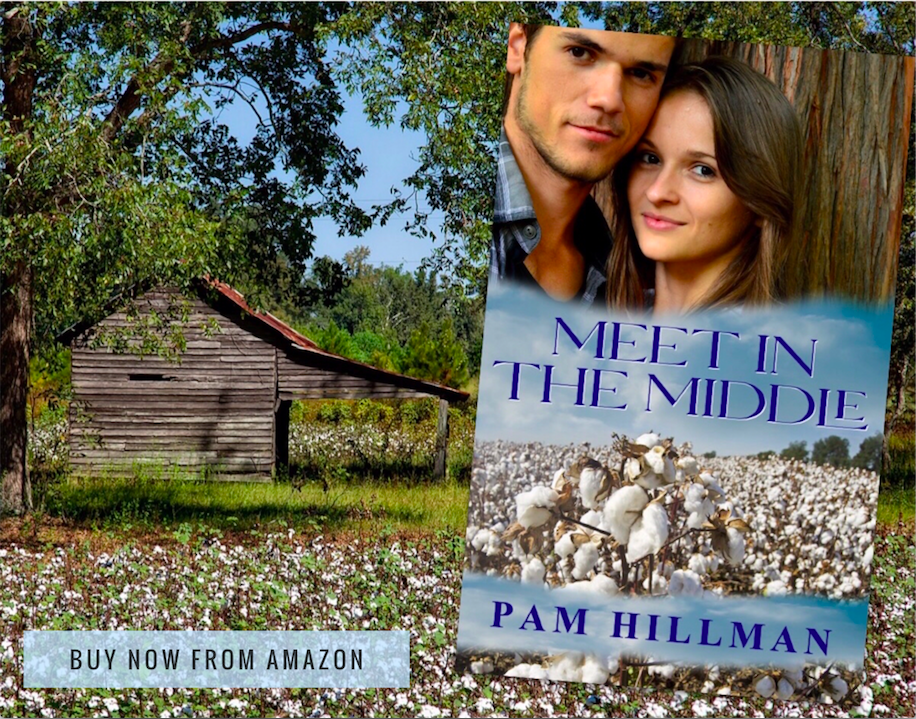

And, just like my parents, Curt Parker and Rachel Garland are struggling to hold on to their land in the late 1800s. They’re not sharecroppers, but they’re both one bad crop away from losing everything.

Meet in the Middle